Edo Bricchetti, a member of IWI’s Council and The International Council for Conservation of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH), has been tirelessly defending the priceless heritage of Lombardy’s historic canals, the navigli, working closely with the responsible authorities for more than 20 years. During this time, although it does not directly manage the canals, Lombardy Region has set up an agency, SCARL Navigli Lombardi, whose task is to coordinate restoration works, develop tourism and promote the heritage of the canals themselves and their corridors; these canals are the ideal vector to visit gems of architecture, enjoy cultural landscapes and see countless vestiges of the industry that for centuries used the abundant waters crossing the plain.

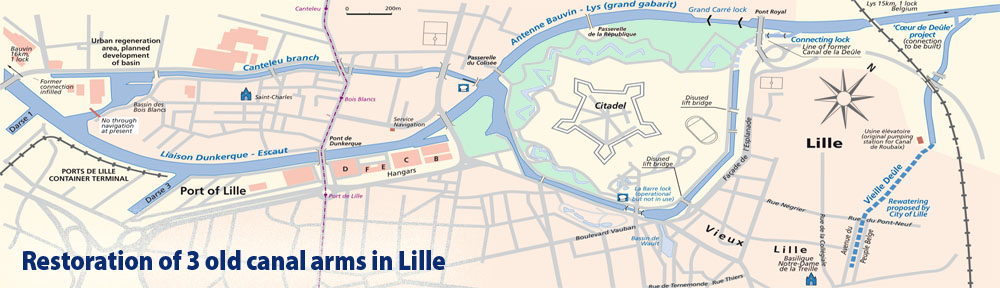

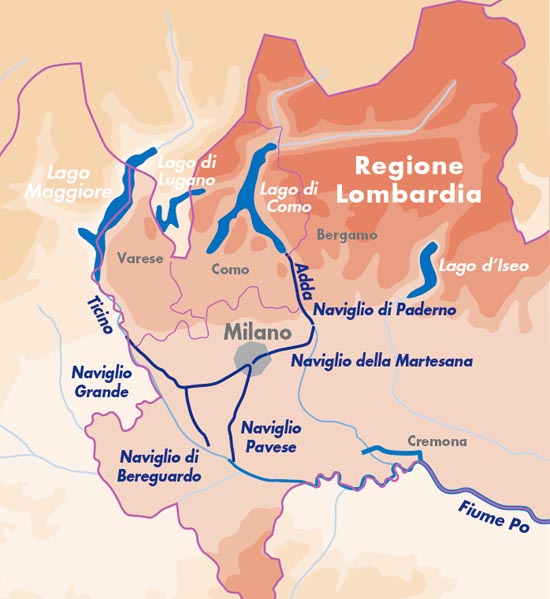

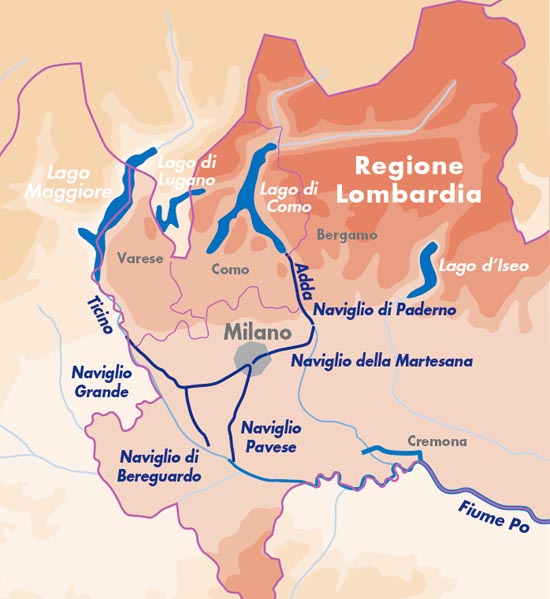

The five navigli between the partially canalised rivers Ticino and Adda

Lombardy at the time of Leonardo da Vinci

When Leonardo da Vinci arrived in Milan in 1482, he discovered works of hydraulic engineering that were already unrivalled in Italy or even throughout Europe. The Viarenna lock, within the city limits, had already been in operation for 40 years, while to the north-east the city was served by the Naviglio della Martesana.

During his 25 years in Milan, Leonardo was to make a significant contribution to improvement of the waterway system which was the most extensive and strategic in Europe at that time.

Between the Ticino and the Po the Padua plain is divided horizontally into distinct sections, between the arid and infertile strip of land to the north and the well-watered lower plain to the south, better suited to agriculture. Springs, irrigation feeders, channels and offtakes conveyed water for irrigation, where formerly spring water and the left-bank tributaries of the Po flowed into stagnant marshes. The canals enabled cultivation of vast areas of arid land to the north of wide tracts of low vegetation and dense heathland. On this network, in the towns, in the villages and countryside, grain mills were established, oil presses, basins for husking rice, paper and felt mills, presses for working metals, tanneries for leather. In short, all economic activity revolved around the waterways, which acquired strategic importance in the regulation of flows for hydraulic energy and for transport.

Lombardy civilisation was founded on this combined use – for industry and agriculture, leading to the development of considerable areas of land, where traditional trades and crafts coexisted with new forms of agriculture, new manufacturing industries, trades and communications.

Brief history of the canal system

Situated roughly half way between the Ticino and the Adda, Milan has always seen these two rivers as potential outlets to the sea through the Po. After abandoning the idea of a direct connection to the broad river through the Lambro, the city concentrated on a system of canals, which were built over a period of seven centuries.

They are divided into two subsystems. The Naviglio Grande, the Naviglio di Bereguardo and the Naviglio di Pavia belong to the Ticino; the Naviglio Martesana and Naviglio di Paderno are connected to and supplied from the Adda. These were linked by the fossa interna or canal ring in the centre of Milan, not unlike the grachten which characterised Dutch cities. Commercial activity was concentrated in the large basins at Porta Ticinese and San Marco.

However, Milan’s dream of becoming a seaport remained unfulfilled for many years, mainly for political reasons, but also on account of objective technical difficulties of navigation (climatic events, irregular river flow regime, problems of water table rise, and competition with nearby cities for control of the waterways). All these obstacles were overcome by the practical approach of the Milanese who already in Roman times, from the second century AD, adapted the smaller rivers Seveso, Nirone and Vettabbia for small-scale navigation.

Ravenna, capital of the Empire of Bysance and Pavia, capital of the eastern Roman empire, served as centres of exchange of produce between the Orient (precious metals, woven cloth, spices and miscellaneous goods) and the West (weapons, timber, construction materials, foodstuffs).

Around the year 1000, Milan, Lodi and Pavia were in bitter competition for access to the river outlets, especially Lodi, protected by the Emperor Federico Barbarossa, and Milan, elected a free City. In particular Barbarossa, who founded the new city of Lodi on 3 December 1158, granted it the status of exclusive port of the Adda. Milan fought bitterly to defend its only access to the Adda through the Lambro, navigable at that time. Inevitably, only three years after the battle of Legnano and the historic victory of Lombardy Communes over the Emperor (1179), the Milanese started work (in the village of Panperduto) on a canal for trade on the left bank of the Ticino. The canal was to transport goods originating from Verbano and nearby Switzerland, thus releasing the city from blockades and imperial control. They were assisted by a flood which, by inundating land near the canal, suggested the extension of the section already built between Abbiategrasso and Landriano (Ticinello, 1157). The limit of navigation was extended in 1187 to Trezzano, in 1211 to St Eustorgio bridge in Milan, and in 1253 to Gaggiano (Naviglio di Gaggiano). The third section, completed in 1257, finally completed the Verbano-Ticino-Milan system.

In 1272 the canal, called the Naviglio Grande, was already in regular use by barges, transporting wood, hay, cheese, cattle, marble and granite to the city, while “exports” upstream included salt, iron, grain and various manufactured goods.

To the south, however, Milan could rely only on the Navigliaccio, completed by order of Gian Galeazzo di Visconti in 1359, for irrigation of Castello di Pavia (and later extended for 8 km to the Certosa di Pavia), and on the Naviglio di Bereguardo, between Abbiategrasso and Bereguardo.

Meanwhile, they applied themselves to connection of the Naviglietto (1156) to the Lombardy waterway network through the Conca di Viarenna (1440) near the lake of Sant’Eustorgio. This connection suggested the future development of a circular canal connecting all the navigli, with the Porta Ticinese canal basin at its centre.

The Incoronata (‘coronation’) lock at San Marco, near Borgo Nuovo at Porta Orientale (built under decrees for reform of navigation by Ludovic the Moor dated 13 October 1496 and 15 April 1497), completed the connection of waters of the Ticino to those of the Adda.

The latter was reached via the Naviglio Piccolo del Martesana, thus named after the county it crossed. Construction of this waterway, of great strategic importance for the city’s economic development, was suggested by the Milanese demand for goods originating in the Valtellina and the Valsassina valleys, especially after the conquests of Lodi and Pavia, from 1335 and 1339. Goods would be carried down the Lario and Adda rivers.

Thus the excavation of the Naviglio del Martesana was completed in only six years, between 1457 and 1463, from Concesa to Cassina de’ Pom. The gradient of the waterway made it possible to provide irrigation offtakes throughout its length, and hydraulic energy for manufacturing works, as well as navigation. The goods transported were principally (heading downstream) coarse and dressed quarry stone, lime, bricks, metals, sand and gravel, weapons and tools in wrought iron, foodstuffs and agricultural produce, wood and coal; boats would return upstream from the city towards the lake with some manufactured goods, but the main cargo was salt. The economic importance of this waterway soon led to the construction of a genuine, dedicated inland port in the San Marco basin in Milan.

However, the waterway suffered from the interruption caused by the Paderno rapids which prevented navigation in the section between Paderno and Cornate d’Adda. Shattered on these rapids were not only a number of intrepid boatmen, but the Milanese dream of uninterrupted navigation from lake Como to the city. Goods thus had to be transhipped and transported overland from Brivio to Trezzo, that is from the confluence of the Lario to the only waterway effectively navigable to the east of Milan, the Naviglio del Martesana.

The French king François I thus decided in 1516 to give the city of Milan 10 000 ducats per year, in support of construction of a new navigable canal, to serve his own political ambitions. Various projects were drawn up, which revived the old idea of a direct link from the lake at Lecco to Milan. A public commission, made up of the engineers Bartolomeo Della Valle and Benedetto de Missaglia, surveyed various solutions which suggested using successively water diverted from the Lambro, then from the Molgora, the Seveso, the Lura and the Olona, and finally, Lake Como. The latter option was chosen, with a choice of two routes: the first was for a major new canal, leaving the river at Brivio and running across the plain via Vimercate and Monza directly to Milan; the second involved using the Naviglio del Martesana and the river Adda from Trezzo to Brivio.

The latter project was judged feasible within space of two years and with the sum of approximately 50 000 Ecus. The Milan Senate decreed on 26 September 1518 to choose this second option, which again was debated between two engineering approaches. Should navigation be developed within the natural river bed, removing all obstacles (using locks in the bed of the river itself)? or should the river bed be avoided in certain sections, by building by-pass canals on the Milanese side of the valley? The second approach, proposed by engineer Benedetto de Missaglia, was chosen. This involved excavation of a canal on the Milanese side of the valley from the locality called Tre Corni to the sacred site of La Rocchetta. Placed in charge of the works was the architect and painter Giuseppe Meda, author (in 1574) of the project for a magnificent structure of masonry, portals and lock-gates in timber, bridges and various mechanisms, capable of overcoming the difference in level of the rapids with a single pound lock featuring separate upstream and downstream gate structures, called castelli d’acque (or ‘water towers’). The downstream structure was originally to be built to a height of 17.82m, while the upstream structure was 5.94 m high. However, various difficulties, compounded by the plague of 1567 and above all by bureaucratic delays, led to abandonment of the initiative.

Construction was in fact approved by the King of Spain only in 1590. The works started between 1590 and 1593 finished in the aftermath of disputes and trials which dragged on between 1596 and 1597. Meda even carried weapons on him as he went about his business, to defend himself.

Meda died in August 1599, and with him all ambitions for completion of the enterprise. The water introduced in the first section in 1603 was drained away completely in 1617, on account of the impossibility of keeping the pound watertight; the inlet was blocked off, the site installations were dismantled and the materials sold off. Under Spanish domination (1525-1748), Milan went through a period of total inertia, again complicated by the bitter opposition of Como and Bergamo to all plans for navigable canals to Milan, which they considered as a serious threat to their own traffics.

Had it not been for the determination of some of Meda’s followers, and for the clear and precise designs of the Austrian administrators, supported by the Italian engineers, the works would never have been completed. It was under the first period of Austrian domination (1748-1796) that the ambitious project for implementation of the Naviglio di Paderno was revived. The studies were revised by count Firmian, representative of the Austrian government in Lombardy, by the adviser Pecis and by mathematicians Antonio Lecchi, Francesco Maria De Regis and Paolo Frisi. Count Firmian, responsible for approval of the works, finally advised minister Kaunitz to accept the bid by the contractor Nosetti (13 July 1773). The project provided for reuse of Meda’s lock foundations, but with the height of the downstream lock reduced to about a third of that in Meda’s original plan.

Nosetti doubted the feasibility of a lock as deep as that proposed by Meda, and envisaged breaking up the difference in level into six pounds instead of two, with the canal’s intake and outlet established respectively at Sasso di San Michele and Valle della Rocchetta.

On 11 October 1777 the canal was opened to navigation amid intense public and official festivities, in the presence of count Firmian, whose inaugural boat proceeded down the canal from Brivo to Vaprio, with the Archduke of Austria also on board. However, a structural failure at one of the locks delayed final opening of the canal until 6th October 1779.

‘Lombardy, a land of engineers never fully appreciated, and of works left incomplete‘

© Prof. Edoardo Bricchetti, 1998, edited by David Edwards-May, 2012

Iron bridge at Trezzo sull'Adda, opened for the Monza-Bergamo railway in 1890; the painting by Carlo Jotti dates from the following year, and shows the entrance to the Naviglio della Martesana in the foreground